Encryption in the Online Safety Bill

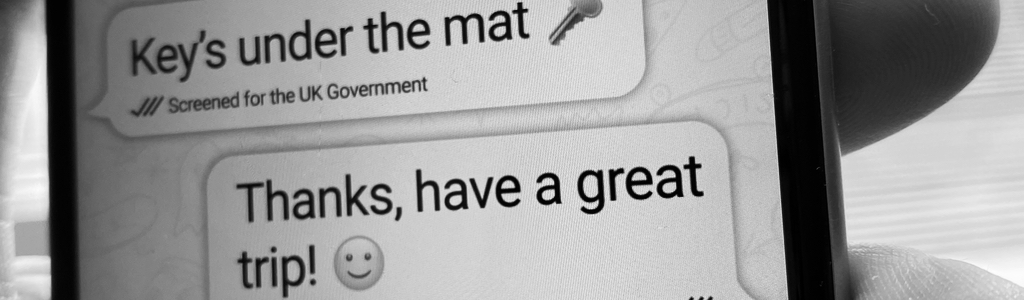

Let’s look at how the Online Safety Bill brings the contents of your private communications into scope for scanning, monitoring, and censorship.

The Online Safety Bill will apply to the contents of the private messages you share with your friends, family, colleagues, and communities. This will apply whether you use standalone services such as messaging apps, or messaging utilities contained within other services, such as direct messaging on social media applications.

Under the Bill, Service providers will have legal obligations to limit the presence and dissemination of illegal content, which means terrorrism and child sexual abuse material, on private messaging services, above and beyond the systems they already use to detect and take down the overwhelming majority of this abhorrent content.

However, as you know, the Online Safety Bill does not just deal with illegal content. It will also oblige service providers to have responsibilities over “legal but harmful” content, meaning free and subjective speech. And in a private messaging context, that means that it is likely that service providers will be required to scan the contents of your private messages for subjective harms.

The only way for service providers to read the contents of your private messages, whether that is for illegal or legal content, will be for them to break end-to-end encryption. That is not an oversight; that is government’s strategy for the Bill.

We have known for a long time that one of government’s goals for the Online Safety Bill is the restriction, if not the outright criminalisation, of the use of end-to-end encryption on private messaging services. This would be enacted to allow private messages to be scanned for the presumed existence of CSE and CSAM.

But once our private messages are unlocked to be scanned for illegal actions, they will also be scanned for legal content, including our personal thoughts and subjective opinions shared as free speech.

We have already discussed how the Bill will grant government with the powers to define what the boundaries of our free speech are, and to do so for purely political reasons. Now add that to the fact that Ofcom will be empowered to force companies to enforce those boundaries, including on our private messages. A failure to do so would mean that these service providers could be found violation of the law, and face penalties, sanctions, and even service shutdowns.

Put simply, there will no longer be any such thing as personal communications. Everything we say, no matter how private, will be fair game under the Bill. Only email and SMS services are exempted; and these are typically insecure in any case.

End-to-end encryption outside private messaging services

In principle, end-to-end encryption outside of personal messaging is out of scope. However, the guiding principle of Government policy is that anything and everything should be in principle readable: this has long been GCHQ’s stated aim.

Other hardliners on this issue include the Health Secretary, Sajid Javid, who has called for Ofcom to “treat high-risk design features like end-to-end encryption as breaches of the Duty of Care and sanctions should be able to apply retroactively.” His report, published while a backbencher, also notes that “It will be insufficient for a platform to argue that introducing such a high-risk design feature will have other benefits in spaces like user privacy and preventing online financial crime.”

Regulatory limits on end-to-end encryption will apply to companies and service providers regardless of their location if they target or serve UK users. This means that data will become easily accessible and subject to misuse. This places both users and businesses at risk, if data breaches occur.

We know that many essential services are considering blocking UK customers, or leaving the UK altogether, rather than be compelled to weaken their data security and act as state snoopers, if end-to-end encryption is compromised or banned under the Bill.

It is also worth noting that government’s strategy on private messaging, and the interception of messages through limitations on encryption, is entirely focused around corporate-provided messaging applications and services. The comprehension of the implications for decentralised services, and open source applications, is nil.

End-to-end encryption as a lever for mandatory age verification

Ahead of the Bill reaching legislative scrutiny, DCMS has published guidance advising service providers to prevent the use of end-to-end encryption on children’s accounts. The thinking here is that if someone under the age of 18 is using an encrypted messaging service, they are either at risk of sexual exploitation or actively involved in it.

But children have as much of a human right to privacy as adults do. So it’s no wonder that TechCrunch has has dubbed DCMS’s advice “No privacy for our kids, please, we’re British”.

As that article noted, one of government’s goals for the Bill is that end-to-end encryption should not be permitted on children’s accounts. But how would a service provider identify children? The Bill will expect all service providers, across all content, to age verify all users, regardless of scope or risk, in order to identify the children, in order to withhold encryption from them. To fail to do so would be a failure to achieve the standards of the Duty of Care, and therefore a violation of the law as it is being drafted.

We will have more to say about that next week.

Hear the latest

Sign up to receive updates about Open Rights Group’s work to protect our digital rights.

Subscribe